October 2 marks 20 years since the D.C. Snipers carried out their first attack in Montgomery County. It was just the beginning of a three-week shooting spree that would terrorize the Washington D.C., Maryland, and Virginia area.

The shooters, John Allen Muhammad and Lee Boyd Malvo, carried out a string of attacks from Oct. 2 through Oct. 24, 2002, murdering 10 people and critically injuring three.

Many of the attacks happened in central Montgomery County, where Muhammad and Malvo shot nine people over the course of three weeks. People who lived in Montgomery County back then remember the life-changing fear amid the indiscriminate killings.

“I do not believe there’s ever been a case that has so profoundly affected our region as this event,” said Montgomery County State’s Attorney John McCarthy. He acted as the lead attorney and legal adviser to the sniper task force at the time. “I think, effectively, if you lived here, you lived differently during those 20 days in October of 2002.”

Week One

The shootings began at 5:20 p.m. on Oct. 2, when the attackers shot through a window of Michael’s craft store in Aspen Hill, narrowly missing Ann Chapman, a cashier at the store. Chapman was unharmed and no alarms were raised.

Almost an hour later, the shooters killed James D. Martin, 55, at 6:02 p.m. at a Wheaton Shoppers Food Warehouse parking lot in Montgomery County. Martin was a program analyst with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

During the morning rush hour the following day, Oct. 3, Muhammad and Malvo gunned down five people, four in Montgomery County between Silver Spring and Rockville in the span of two hours, from 7:41 to 9:58 a.m.

The first victim was James “Sonny” Buchanan, a 39-year-old landscaper, who was shot dead while mowing the lawn of Fitzgerald Auto Mall in North Bethesda at 7:41 a.m.

Not even thirty minutes later, Muhammad and Malvo killed Prem Kumar Walekar, a 54-year-old taxi driver while he was pumping gas in his taxi at a Mobil station in Aspen Hill.

At 8:37 a.m., Sarah Ramos, 34, was killed after getting off of a bus and reading on a bench at the Leisure World plaza in Silver Spring. She was a housekeeper and a babysitter.

The final victim in the morning shooting spree of Oct. 3rd was Lori Ann Lewis-Rivera, 25, who was murdered while vacuuming her minivan at a Shell station in Kensington at 9:58 a.m.

By the afternoon, the attacks were linked by the Montgomery County Police Department (MCPD), prompting a massive multi-agency investigation. The victims in every attack were struck by a single bullet shot from a certain distance before the killers vanished.

“This kind of series of victims who lost their lives doing things that everybody else was doing was terrorizing to this area, in that it was the kind of thing that people could relate to,” said Lucille Baur, the Deputy Director of the MCPD public information office and one of the police spokespeople at the time.

“It wasn’t as though this was an extreme situation that they personally would never find themselves in. These were everyday situations that anybody could find themselves in. So it really hit home to have so many people shot and killed in such a short amount of time.”

That evening on Oct. 3, Pascal Charlot, a 72-year-old retired carpenter, was killed walking down the streets of Washington D.C. After this attack, over 400 agents around the country were working on the case. The attacks had breached the D.C. jurisdiction, causing federal agencies to become involved.

Only 13 months after 9/11, fears rose amid worries that another terrorist attack was underway. “I don’t think we knew for sure we weren’t dealing with a different form of a terrorist attack,” said McCarthy. “ I think that’s why all of the federal authorities immediately came running to us that day… the ATF was there, the FBI was there. They were there immediately.”

The initial wave of attacks spurred deep fears in the public. Each victim had been murdered while doing mundane activities and it began to seem like merely going outside was to gamble with random horror.

“Muhammad was really trying to create a terrorist atmosphere, which he was able to do because everybody was walking on eggshells,” said former Maryland attorney general Doug Gansler, the chief prosecutor for Montgomery County at the time

“People were ducking when they were filling up their gas tanks, people were walking zigzagging into the supermarket when they were going grocery shopping. It really actually affected our area, in some ways, more directly than 9/11.”

After 3 tense days, on Oct. 7, 13-year-old Iran Brown was critically injured after being shot outside his middle school in Bowie. Following the attack, the Chief of Police for Montgomery County Charles Moose issued a code blue alert for all Montgomery County Public Schools (MCPS), requiring children to remain indoors at all times. MCPD also increased security presence on school grounds.

“It was a beautiful October 2nd to the 22nd,” said Gansler, who had children in school at the time, “and the kids were not allowed to go out for recess. They were all locked down to the schools and they were young, they didn’t understand it.”

Although Moose informed residents that schools were safe, many parents resorted to picking up their children early from school. Field trips were postponed.

Baur pointed out that Iran Brown marked a “turning point” in the series of shootings. “This was an innocent child on school grounds.”

“This was kind of a loss of innocence for children,” Baur continued. “Families try to protect their children from the worst that is happening out there in the world, but they knew something was going on. Schools were going into lockdown situations, recesses were canceled, and high school football games and practices were canceled.”

Conflicting reports led the police on a wild goose chase, until the Oct. 7 attack left them with their first solid clue. Near the middle school in Bowie where the boy was shot, press personnel covering the scene found a tarot card with the phrase “Call me God” written on it. With it was a letter with a chilling message:

“For you Mr. Policeman

‘Call me God’

Do not release to the press…

p.s. your children are not safe”

The letter from the sniper demanded that $10 million be deposited into a listed bank account. Additional messages from the snipers relayed similar rhetoric: children were not safe.

Week Two

The media released images of the tarot card and the letter before handing it over to investigators. Moose, who headed the investigation on behalf of MCPD, began to have a tenuous relationship with the growing media presence. He had not intended for the tarot card to be released.

In his book Three Weeks in October: The Manhunt for the Serial Sniper, Moose recalled the relationship. “There was a chance to build that trust, and then by having the media put [the tarot card] out there, it just felt like any attempt at communication, any attempt at building that trust had been destroyed.”

The media release of the tarot card was a “devastating blow” to the investigation, said Baur. “When you’re dealing with indiscriminate shooting and you have a clue believed to be from the shooters themselves that says ‘do not release to the press,’ then that is definitely guarded evidence. We did not know then what would happen next.”

On Oct. 9, Gaithersburg resident Dean Harold Meyers, 53, was killed while pumping gas in his car near Manassas, Virginia. Kenneth Bridges, father of six, was also pumping gas when Muhammad and Malvo murdered him near Fredericksburg, Virginia on Oct. 11.

As FBI hotlines became overwhelmed with the deluge of tips, one of their own, FBI Analyst Linda Franklin, was gunned down while she and her husband were loading their car in a Home Depot parking lot in Falls Church, Virginia on the night of Oct. 14.

Week Three

Jeffrey Hopper, 37, was walking with his wife through a Ponderosa Steakhouse parking lot in Ashland, Virginia on Oct. 19 when he was shot. He survived.

Three days later, Muhammad and Malvo killed their last victim, Conrad Everton Johnson, a 35-year-old Silver Spring bus driver, while he was standing on the steps of his bus in Aspen Hill.

With the tenth death, pressure on authorities reached a fever pitch. Further, no one knew that Johnson would be the final victim.

“It was very real for me, seeing the pain these families felt, feeling the loss they had experienced,” Moose wrote. “It made the case all the more human and horrible.” It also became clear that there was no possibility of feeling joy at the prospect of finding the killers.

Around the time of the last shooting, a caller claiming to be the sniper phoned the police. The caller, discovered later to be Malvo, claimed responsibility for a liquor store robbery in “Montgomery.” After wide speculation, investigators discovered he had been referring to a shooting in Montgomery, Alabama.

The separate attack on Sept. 22, 2002, less than a month before the first Maryland attack, had occurred outside an Alabama liquor store. The manager, Claudine Parker, was killed.

Working in collaboration with the Mobile, Alabama office, which had the record of the incident, the FBI was able to identify Malvo’s fingerprints on a magazine left at the scene. Authorities were able to link Malvo to Muhammad and identify them as the prime suspects.

On Oct. 23, authorities released a late night alert for two men in a blue 1990 Chevrolet Caprice with New Jersey plates.

Around 3:15 a.m. the following morning, police located the snipers as they slept at a rest stop off Interstate 70 near Myersville. They arrested 41-year-old John Allen Muhammad and 17-year-old Lee Boyd Malvo without a struggle.

“No one expected a peaceful resolution, everyone expected that the snipers would go out in a blaze of gunfire,” said Baur. “The officers that responded to the scene knew that they were really putting their lives at risk.”

Gansler echoed that sentiment, saying that he never thought the snipers would live. “They were thought to be killed by, you know, death by police or suicide by police,” he said.

After the arrest, authorities investigated the blue 1990 Chevrolet Caprice and discovered a modified backseat and trunk compartment. Resting in the hidden compartment was the suspected murder weapon, a .223 Bushmaster rifle.

FBI pictures of the vehicle show a small hole drilled above the rear license plate as a line of sight to view through a gun scope. The distressed look of the car and the small hole made it inconspicuous from a distance and allowed the attackers to escape the crime scenes swiftly or to wait nearby until the police activity was over.

(Chevrolet Caprice/FBI)

After the snipers were taken into police custody, the horror in the DMV area finally came to an end. “There was monumental relief,” said Baur. “For me, tears, I mean there was tremendous pressure throughout this investigation. Emotions ran high. Everyone was exhausted.”

Pretrial

With the press closing in on every tip regarding the location of the shooters, authorities moved Muhammad and Malvo to an offsite building for questioning. “We didn’t take them to the police headquarters because of the media circus,” said Gansler. “We brought them to an office park for juvenile justice to interview.”

Authorities struggled to get Muhammad to admit involvement in the crimes. Malvo, on the other hand, eventually opened up and admitted guilt.

Prosecutors now had grounds for a trial.

Before a trial could begin, prosecutors worked to decide which jurisdiction Muhammad and Malvo would be tried in. Prosecutors sought the maximum punishment. The two were both extradited from Maryland to Virginia.

“Virginia had an available death penalty for both participants in the sniper shootings,” said McCarthy. “We had already outlawed the death penalty at the time for those under the age of 18, so Mr. Malvo would never have been eligible for death in Maryland.”

Trial

When Muhammad’s trial came about a year after the arrest, a jury heard from more than 130 witnesses and saw over 400 pieces of evidence. The prosecution had one major hurdle to overcome to get him convicted on specific charges: they were unable to prove which shooter committed each of the murders.

Virginia state attorneys ultimately brought four charges against Muhammad. On Nov. 17, 2003, he was convicted of all of them: one count of first-degree murder, murder with the intent to terrorize the government or public, conspiracy to commit murder, and the illegal use of a firearm.

In a Virginia courtroom on March 9, 2004, he was sentenced to death for the murder of Dean Meyers. Muhammad was later executed by lethal injection on Nov. 10, 2009.

After a separate simultaneous trial, Malvo was convicted of capital murder in the state of Virginia and sentenced to life in prison without parole. A 2012 U.S. Supreme Court ruling determined mandatory life sentences for juveniles are unconstitutional, allowing Malvo to request new sentencing hearings. He requested parole in August of 2022 but was denied.

“I think this would be a really tough case for someone to reduce his sentence and have him released back into the community, simply because of the sheer volume of victims that were in these cases,” McCarthy stated.

Malvo remains in prison to this day.

Regardless of Muhammad and Malvo’s sentencing, this community lacked a sense of justice. “This thing has left an emotional scar on this community that remains 20 years later,” said McCarthy.

Bob Meyers, the younger brother of victim Dean Meyers, spoke about their family’s feelings of closure amid their loss. “We believe that the justice system worked and it took the situation to its appropriate end,” he said. “But as far as closure, personally, you only get that if you get your relative back and we’ll never have that.”

He recalled fond memories of his brother and spoke of their connection as young kids. “He taught me to ride my bike, I learned to play baseball under his tutelage,” he said. “So we were truly brothers in that sense.”

Charles Moose gained national fame and acclaim as the face of the investigation. He signed a lucrative book deal to write about his experiences shortly after Muhammad and Malvo were apprehended.

The Montgomery County ethics commission ruled that taking money from a publisher violated a law that prohibits county officials from profiting off of their positions. After the controversy, Moose resigned as chief of police for Montgomery County in June 2003 . He was paid $170,000 to write the book and received a $4-per-book royalty.

Moose later worked as a patrolman for the Honolulu Police Department from 2006 to 2010 before retiring to Florida. He died while watching a football game in his home in Palm Harbor, Florida on Nov. 25, 2021, according to a Facebook post by his family. He was 68.

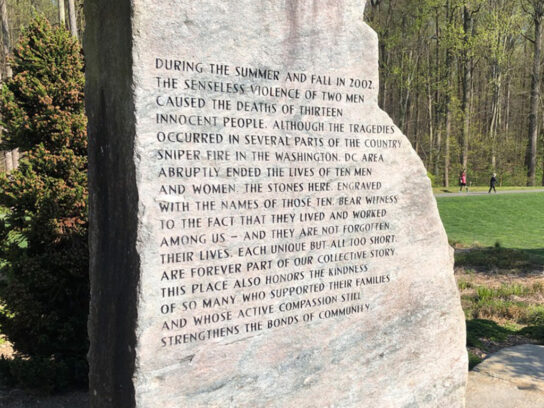

The community remembers the 10 victims of the attacks and extends sympathies to families coping with heavy loss. “Every single life that was lost was personal to all of us, there was no jubilation when it had come to an end,” said Baur.

MyMCM has produced a one-hour show called “3 Weeks of Hell”: The D.C. Sniper Attacks, 20 Years Later that debuts Friday, Sept. 30 at 7 p.m. on MCM cable channels 21 (SD) and 995 (HD) and MCM’s YouTube page. The show will also be on mymcmedia.org and all of MCM’s social media platforms.

Comments are closed.