A Royal Refuge, Brideshead Revisited, and a 170-Year-Long Lawsuit

Recall from two earlier monthly columns that Thomas Ligon/Lygon, the progenitor of the American Ligon line, is my proven great-g-g-g-g-g-g-g-g-grandfather, and I recently attended a Ligon/Lygon family reunion in England. Telling the story of the Lygon/Ligon family and Madresfield Court, which dates back 900+ years, would likely take 900 pages, so I will just relate three famous episodes.

The Royal Refuge

Madresfield Court, ancestral home of the Lygons, has twice been designated as a Royal Refuge. The first time was during the reign of King George III, when there was fear of a Napoleonic invasion of England, and the royal family called on their Lygon cousins to provide them with a safe location away from London and the south coast. Madresfield Court, with its medieval moat, was officially designated a Royal Refuge. Thankfully the danger passed before it was needed.

The second time was during World War II. The Nazi Luftwaffe bombed England, London, and even Buckingham Palace, and the royal family was living under the threat of invasion. Once again, Madresfield Court was again chosen as a Refuge. The worst-case backup plan was that the royal family were to be taken to Canada, to Hatley Castle at the southern tip of Vancouver Island, if the German invasion succeeded, so the British government-in-exile and the Monarchy could continue fighting from abroad.

A super-secret evacuation unit, called the “Coats Mission” under Olympic athlete and Major James Coats, MC, 3rd Baronet, was organized. This special unit included a company of the elite Coldstream Guards, a troop of 12th Royal Lancers with eight Rolls Royce and Daimler armored cars, and a squad of military police riding Norton racing motorcycles. Their mission was to escort the royals from London to Madresfield, and if necessary on to Holyhead, Wales, on the Irish Sea, for pickup by the Royal Navy.

Brideshead Revisited

Madresfield and the Lygon family inspired Evelyn Waugh (who visited the manor house frequently) to write what Modern Library selected as “one of the 100 greatest novels of the 20th century,” Brideshead Revisited. The 1945 novel, using much of Waugh’s original dialogue, became a famous Granada Television/PBS series of the same name in 1982, starring Jeremy Irons and Anthony Andrews. It was rated as the best-ever British TV series by The Telegraph newspaper in 2015. It was filmed at Castle Howard in Yorkshire, a much larger, more formal and grandiose structure than Madresfield Court.

Brideshead Revisited is a thinly disguised description of Madresfield and the family life of William Lygon, KG, KCMG, CB, KStJ, PC, 7th Earl of Beauchamp. In the novel, he is the Marquis of Brideshead Castle, who wanted a divorce from his wife, but she refused on account of their Catholic religion, so he left for Venice, where he lived with his Italian mistress and was shunned by British society.

In reality, William Lygon (1872-1938) was one of the most powerful men in the country, whose precipitous fall was so disgraceful at the time that it had to be kept secret and could not be published, even in a novel. He was sword bearer to King George V at his coronation, Governor of New South Wales, Australia from 1899 to 1901, and later a member of the Privy Council, Lord President of the Council, an effective Liberal Party cabinet minister responsible for all public works and housing, and a Knight of the Garter.

Sadly, his homosexuality was outed in 1931 to King George V by Lygon’s own brother-in-law and Tory political rival, the Duke of Westminster, who was trying to disgrace the Lygons and the Liberals. It worked. William Lygon was quietly and quickly told that he must flee England within six hours, or face imprisonment for two years under the “gross indignities” statute or ten years at hard labor or even life in prison for violating the “buggery” (sodomy) statute. King George was horrified at the revelation, saying, “I thought men like that shot themselves.” The King then forced his son Prince George, Duke of Kent, to cut off his budding relationship with Mary Lygon, daughter of William.

William Lygon resigned from all his government posts, lived in Europe and died in New York. After his departure for Europe, Lygon’s brother-in-law sent him a telegram that read, “Dear Bugger-in-Law: You got what you deserved. Yours, Westminster.”

The 170-Year-Long Chancery Case of William Jennens “The Miser”

The Lygon family was always well off, but received a huge financial boost in 1821 when William Lygon, FRS, 1st Earl Beauchamp (1783-1823) inherited a substantial portion of the infamous William Jennens (or Jennings) estate. Jennens, known as “William the Rich” or “The Miser of Acton,” was the wealthiest commoner in England when he died intestate and without children in 1798, at the age of 97. He had made much of his money by lending money at usurious rates to asinine aristocrats addicted to gambling. He was so miserly that he lived in the dank basement of his run-down mansion with his dogs and two servants, never entertained, and rarely went outdoors. According to his favorite servant, Jennens was returning home from his soliciter’s to retrieve his spectacles, in order to sign his will, which was found unsigned in his pocket after he died.

The resulting lawsuits lasted until at least 1980, or 170 years, a world record. Some people named Jennens or Jennings to this day still think they are owed money from the estate.

The second Earl Beauchamp inherited from Jennens because he was allegedly one of only two remaining first cousins once removed of the Miser – although some parties still dispute this assertion.

The case attracted so much attention that thousands of people from England, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand and the United States formed clubs of anyone with any possible connection to the family. Members invested sums to hire lawyers to contest the case. The most famous American claimant was the US Secretary of State and Presidential candidate, Senator Henry Clay. None got a ha’penny. Only the lawyers got rich.

The case inspired Charles Dickens, who worked in the Court of Chancery in London when the case was only 50 years old, to write his classic novel Bleak House. He called the case Jarndyce v. Jarndyce, and his story is a devastating attack on lawyers, the courts system, and greed.

Madresfield Court is usually open for public tours for about 40 days per year during the summer. Contact: tours@madresfieldestate.co.uk for specific dates and times in 2024.

Photos courtesy Lew Toulmin

- A. Madresfield Court was designated as an official Royal Refuge for George III and his family (seen here in a painting by Johan Zoffany) during the Napoleonic Wars. It was chosen for its location away from the south coast, for its moat and defensible walls, and because of the close links between the royal family and the Lygons. It was never used for this purpose.

- B. King George VI, his wife Queen Elizabeth, and Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret in World War II. In case of a Nazi invasion, their Royal Refuge was Madresfield Court – or Canada.

- D. Portrait of author Evelyn Waugh as a young man. He wrote Brideshead Revisited, rated as one of the best novels of the 20th century. He converted to Catholicism in 1930 at the age of 33 after the failure of his first marriage, served in World War II in the Royal Marines and Royal Horse Guards, and participated in wartime commando operations in Senegal, Crete and Yugoslavia, but distained military bureaucracy and inefficiency. He ruffled political feathers by reporting that Tito, who was being supported by the Allies, was closing down churches and murdering Christian priests.

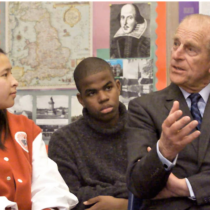

- E. Young Jeremy Irons and Anthony Andrews starred in the 1982 TV series “Brideshead Revisited,” named by many publications as one of the greatest British television series of all time. The TV series and underlying novel were inspired by the Lygons and Madresfield Court.

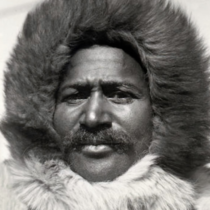

- F. William Lygon, KG, KCMG, CB, KStJ, PC, 7th Earl of Beauchamp, one of the most powerful men in England, was outed for homosexuality in 1931 and had to flee England immediately and permanently, or face possible imprisonment for life.

- G. Hugh Grosvenor, GCVO, DSO, 2nd Duke of Westminster, was one of the wealthiest men in the world. In 1931 he outed his brother-in-law William Lygon for homosexuality, forcing him to flee England. Westminster was pro-German and virulently anti-Semitic, and in 1943 he and his former mistress Coco Chanel (a Nazi collaborator and probable Abwehr spy) unsuccessfully tried to broker a peace agreement between Churchill and Hitler.

- H. Certificate for “investors” who would give money to American lawyers to make claims for the massive, disputed Jennens “The Miser” fortune, and would then be guaranteed a share in the “winnings.” No investors got any results.

- I. An original first edition of Charles Dickens’ Bleak House, serialized in 1852-3, on sale on Abe.com for $9500. This novel was inspired by the 170-year-long Jennens case.

Comments are closed.